Art Lesson 37, Part 4

Who were Titian’s Colleagues and Competitors. Competition during Renaissance

Learn how to paint like the Old Masters!

Old Masters Academy Online Course

Self-study, self-paced online video courseLifetime membershipOne-time payment: $487Enroll Now!Personal Tutoring online + Online Course

Unlimited tutoring by the Academy teachersLifetime membershipOne-time payment: $997Enroll Now!« Back to the Art Lessons List

Titian’s Colleagues and Competitors. Competition during Renaissance

During Titian’s time, there was fierce competition among artists for commissions and a drive to dominate the art scene. In times when high standards meant a lot, every ambitious artist strived to excel in his mastery over his competitors and win commission. So, rivalry was a real deal. The first who started used the term “competition” in conjunction with its economic factor was Vasari. He used the term repeatedly, stressing its importance in developing a high level of standards.

The competition, at the time, can be illustrated by the following statistics: In the late fifteenth century, in Florence alone, there were more woodcarvers than butchers. At one time, there were 54 workshops for marble and stone craftsmen, 44 master gold- and silversmiths, and at least 30 master painters with their crowded workshops. At the same time, Venice contained so many painters, of all descriptions, that it could support several shops that supplied pigments and other art materials.

Artists were scrupulously following what their competitors were doing; they fished around for ideas and, from each other, they borrowed ideas for their compositions. Titian wasn’t an exclusion. He also borrowed, and other artists borrowed from him as well. This natural circulation of ideas led to new interpretations of reputed formulas.

Let’s look at Titian’s painting, in which the influence of other masters is clearly traced.

In the young Titian’s fresco, The Miracle of the Jealous Husband, the figure of the woman correlates with Michelangelo’s Eve on the Sistine Ceilings. This is not the only example of Titian borrowing from Michelangelo.

Entombment of Christ was inspired by Raphael, who, in turn, based the image of Christ on the figure in Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

Worship of Venus by Titian was directly influenced by the preliminary drawings by Fra Bartolomeo.

He also borrowed from relatively MINOR artists. For example from Giulio Romano, he borrowed ideas for the composition of his Flaying of Marsyas.

In some cases, when painting portraits, he used another artist’s portrait as the basis for his own. This was done with the Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, the wife of Charles V.

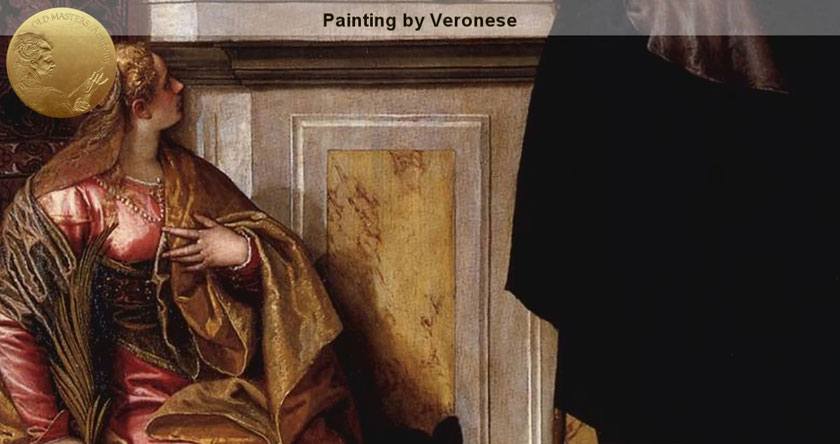

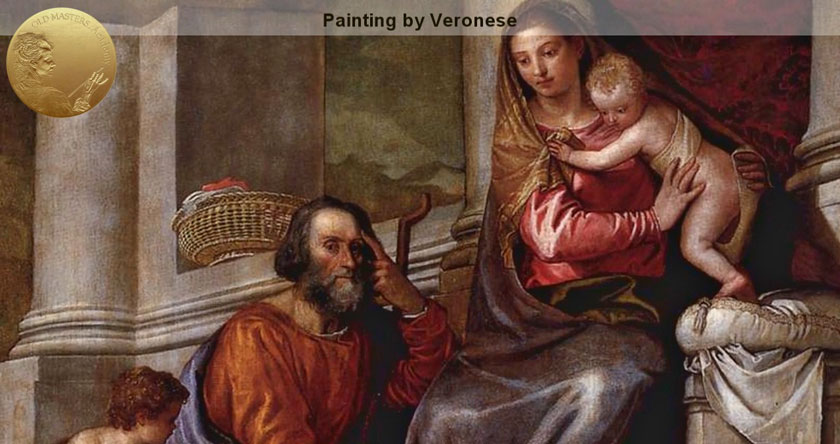

Titian was also an object for admiration, and his contemporaries and artists of future generations often borrowed from him. A twenty-three-year-old Veronese, at the beginning of his career, painted this altarpiece, that was based on Titian’s famous Pesaro Altarpiece, which was created some thirty years before.

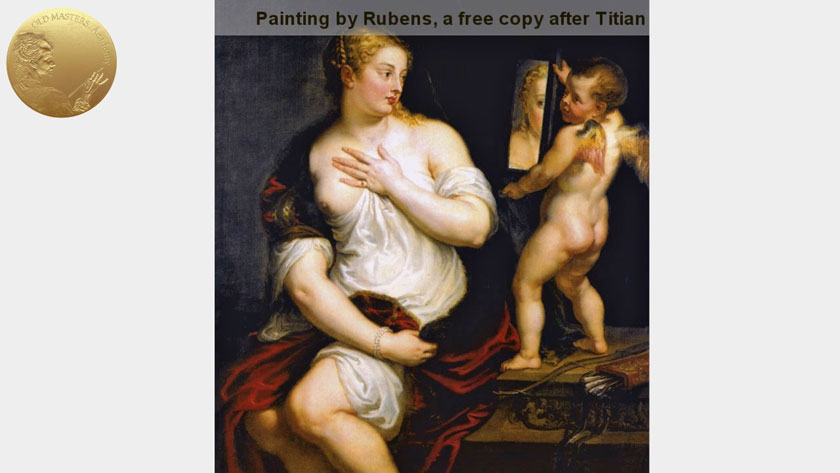

Rubens was the greatest admirer of Titian. Already a mature and famous master, Rubens used any opportunity to learn from Titian by copying his artworks.

Thus, when he was on a diplomatic mission in Spain, he was compelled to remain in Madrid for more than seven months. He spent that time productively by copying all the paintings by Titian in the royal collection. At that time, he was already fifty-one years old and a successful painter and diplomat.

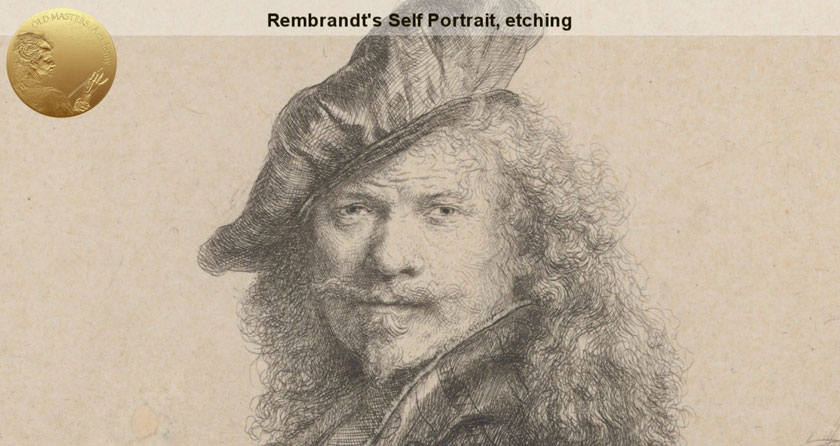

Another eminent admirer of Titian was Rembrandt, who never visited Italy and saw just few original paintings by Titian; however, he was familiar with Italian art and Titian, particularly via engravings. The composition of his celebrated Self-portrait at the age of 34, was borrowed from Titian’s Man with a Quilted Sleeve. Rembrandt happened to see this painting at an auction in Amsterdam one year earlier.

As you may have noticed, all these collective borrowings from each other wasn’t considered “copying”, but new variations were transformed into their own artwork.