Art Lesson 37, Part 13

Discover all about Underdrawing in Titian’s Paintings

Learn how to paint like the Old Masters!

Old Masters Academy Online Course

Self-study, self-paced online video courseLifetime membershipOne-time payment: $487Enroll Now!Personal Tutoring online + Online Course

Unlimited tutoring by the Academy teachersLifetime membershipOne-time payment: $997Enroll Now!« Back to the Art Lessons List

Underdrawing in Titian’s Paintings

One of the most important questions artists are eager to know the answer to, is how to actually start the creative work: should they transfer the preparatory drawing onto the canvas (if they have one)? Do they have to transfer a cartoon, or draw with a brush, directly on the canvas? Or do they need to skip underdrawing and start painting straight away, as this is traditionally believed to have been the Venetian school’s approach during the Renaissance.

There are a number of ways to start, but let’s explore the approach typically used by Venetian artists.

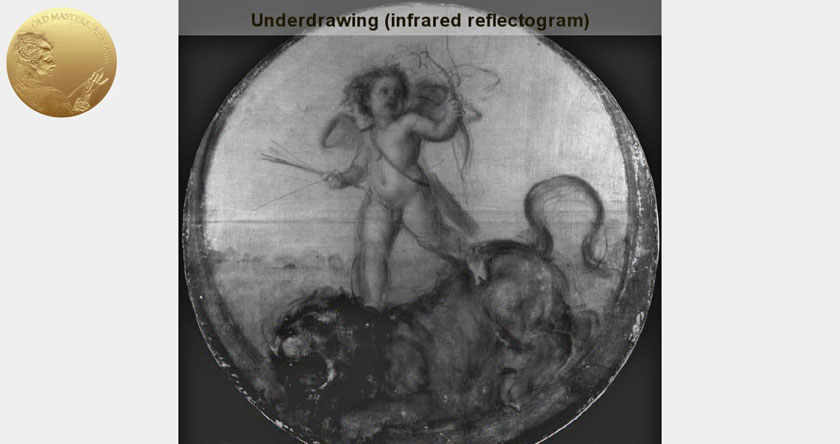

So, what was Titian’s way to start an artwork? Modern scientific methods revealed that Titian did not paint his works directly with paint and colour. Instead, he started with underdrawing.

The myth about Titian’s drawing “disabilities” had spread, thanks to Vasari’s anecdotes published in “Lives.” According to Vasari, Michelangelo, after seeing Titian’s Danaë, told him in a private conversation that it would be helpful to Venetian artists to learn to draw.

Vasari was advocating the Florentine method of painting, with the usual procedure beginning with a design for a composition and then refinement through many drawings. This leads to the creation of an actual size detail cartoon, which was finally transferred onto a canvas. This way, the composition was decided on before the first stroke of the paintbrush.

Vasari totally disagrees with the Venetian method of painting, in which they paint directly on the canvas without the intermediary step of well-developed cartoons.

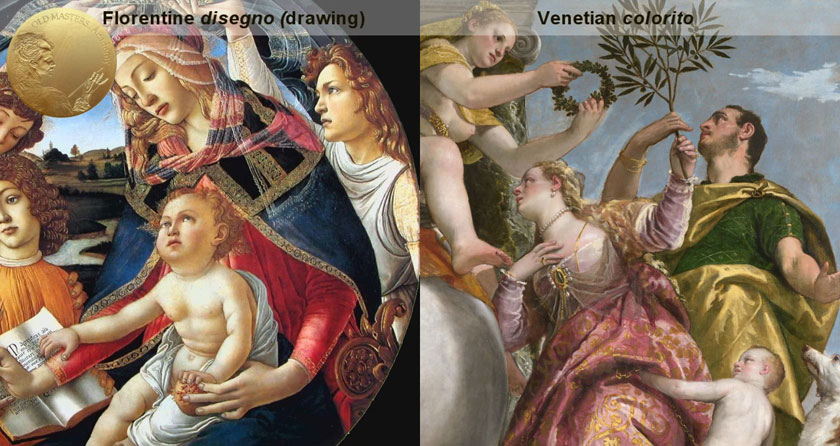

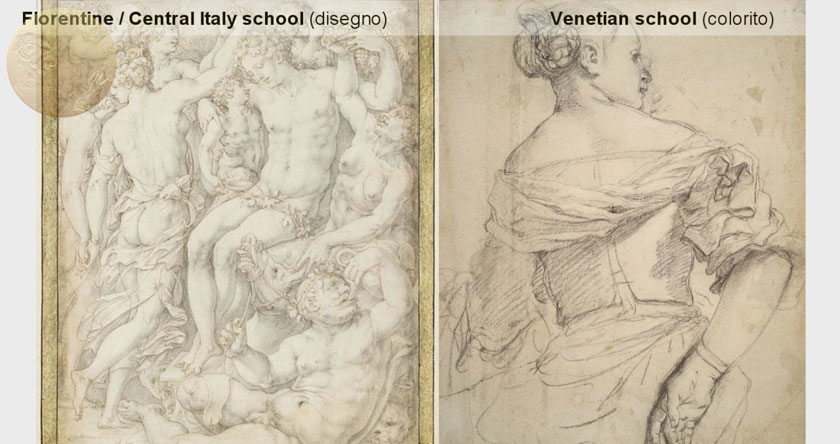

Two opposite and competitive schools clashed on painting methods – the Florentine was based on disegno (drawing) and the Venetian employed colorito.

Representatives from each school were confident that their method was the correct way. So, Vasary was extremely interested in making the Florentine approach a superior over the Venetian way. Venetians were rivals to them, with different values and standards. So, Vasari hadn’t managed, and probably hadn’t even tried to maintain, a neutral point of view when describing the competitors.

I’m not even mentioning that Vasari hadn’t include Titian in his first edition of the “Lives.” It was like Titian didn’t exist at all. Such an exclusion reveals even more than other critical comments. At the end of the day, Vasari couldn’t put Titian down, as it was very obvious that he was genuinely great in painting. So, Vasari afforded a little naughty comment on behalf of Michelangelo.

Now, everyone quotes, without any filtering, what Michelangelo reportedly said. Titian, in turn, didn’t have a chance in Vasari’s book to speak out about Michelangelo’s skills.

I personally refuse to take for granted such a comment about Titian’ abilities. Yes, in the earlier phase of his career, he was sometimes awkward in his draftsmanship, but in general, his paintings proved that he was a proficient master of figure painting. It’s foolish to admit that an artist who created such masterpieces was unable to draw. Despite the seeming dissimilarities between Florentine disegno and Venetian colorito, we should not polarise them.

There is enough evidence that Venetians did drawings and their draftsmanship was at least equal, if not greater, to Florentine artworks. However, their preliminary drawings were mostly done directly on canvas in charcoal or with a brush. An X-ray analysis confirms that in the 16th century, Venetian artists, including Titian, worked empirically, finding and correcting painting compositions straight on the canvas. There are many examples of re-worked and substantially modified drawings that are hidden beneath painting layers.

Thus, both in Florence and Venice, drawing was an important part of an artwork’s creation process; although the two schools used different approaches. In Florence, drawing was correct, refined, and idealized while drawings by Venetians were rather a “vision in progress” as opposed to polished sketches.

Now, let’s look at specific examples of Titian’s artworks. The style of Titian’s underdrawings remains very consistent throughout his long, creative life. The most typical technique for Titian was the application of broad, freely fluid lines that suggest the form or just a few short strokes, rather than a precise outline (this was usually done by brush).

An infrared analysis of Titian’s works shows that he drew with a brush and a liquid medium with a carbon black pigment. This black paint is visible with infrared rays.

Such frivolity was unthinkable before Titian; the older generation of other Venetian artists, like his teacher Giovanni Bellinior, even same generation counterparts Giorgione and Sebastiano del Piombo (who were just about 5 and 12 years older, respectively, than Titian), still followed the tradition of making an accurate underdrawing.

However, in some cases, when precision was needed for especially refined compositions, (Bacchus in Bacchus and Ariadne), the lines were quite precise.

The analysis of cross-sections show that in most cases, the underdrawing was done on top of an imprimitura layer.

When Titian was working on a completely unique composition, he always worked freehand, sketching the objects and figures by eye. He was able to reposition objects and figures multiple times during a painting. (Cupid in The Triumph of Love). There is no evidence that Titian ever used mechanical methods for transferring drawings from cartoons.

However, there were exceptions. It has been revealed that in workshop replicas and variations of his most successful compositions, carefully executed and precise underdrawings were probably transferred by the means of tracings.

In the Christ and the Adulteress, the underdrawing was quite approximate and the artist improvised and changed almost every head in the composition design to animate the story.

The Appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene features the drawing with undefined hands and feet. For Saint Sebastian, Titian did separate studies of the hands and feet on a larger scale. This drawing was done over an imprimatura. Christ’s features were drawn quite precisely with the point of a brush.

The Holy Family with a Shepherd – An infrared reflectogram reveals a scribbled underdrawing, with chaotic lines, was created for the Virgin’s shoulder. There were changes in the composition of this area. Joseph’s hand was drawn with loose, thick lines. Part of this drawing was later covered by the paint of the Child’s legs.

The Man with a Quilted Sleeve presents very little underdrawing in the face. The man’s right eye and eyebrow were originally lower; also, the face outline and tip of the nose were adjusted. His hairstyle was sketched with a few strokes. The face was originally wider, and then was corrected by covering it with the background colour, which was applied as a thicker layer close to the face’s edge.

The bulky sleeve was outlined with long, flowing brushstrokes and the model’s shoulder was originally drawn slightly lower than painted. The broken quality of lines suggests that the underdrawing was done over the imprimatura.

Portrait of a Lady – The broad lines in the woman’s dress, around her neckline and shoulders, indicate that originally, a twisted scarf had been planned there, but later, Titian abandoned this design and decided to expose more of her shoulder.

Bacchus and Ariadne – It is hard to believe that Titian did this complicated composition without preliminary sketches on paper. In the X-radiograph images, there is no trace of alterations to the figures of Bacchus, the Laocoön, the woman with the cymbals, and the satyr. They were painted without any major alterations. At the same time, two cheetahs were sketched with rapid, fluid brushstrokes and the position of their feet had been altered by the artist. Also, the infrared reflectogram shows that the barking spaniel was added over the foreground and the chariot wheel at a later stage. The bacchante playing the cymbals was also amended when Titian experimented with the contours of the drapery folds several times.

In the The Triumph of Love, we see an underdrawing, typical of Titian. The leg’s position was changed several times, leaving multiple outlines. Fast lines were made with a dry brush in black paint, touching the raised canvas weave.

Metropolitan’s Madonna and Child has an energetic underdrawing. The position of the Child was originally marked on the right in an upright, sitting posture. It resembled compositions by Bellini, including the Metropolitan’s Madonna and Child, Titian later decided to move the Child’s figure to the left, into a reclining position. The Virgin bends over him in a tender gesture, with mother and son looking at each other. Later, the artist changed the composition once again, with the baby looking away from his mother.

The lines of an underdrawing in The Vendramin Family are now visible through the paint layers. The outlines were rapidly sketched with black, painted brushstrokes to define the pose of the figures.