by Rosily Roberts

Rembrandt’s technique and artistic practices are well documented and well-known. His mastery of paint, his emulation of the Italian masters, and his incredible rendering of human emotions are what have ensured his place among the most revered artists of history. However, his personal life is as interesting as his art.

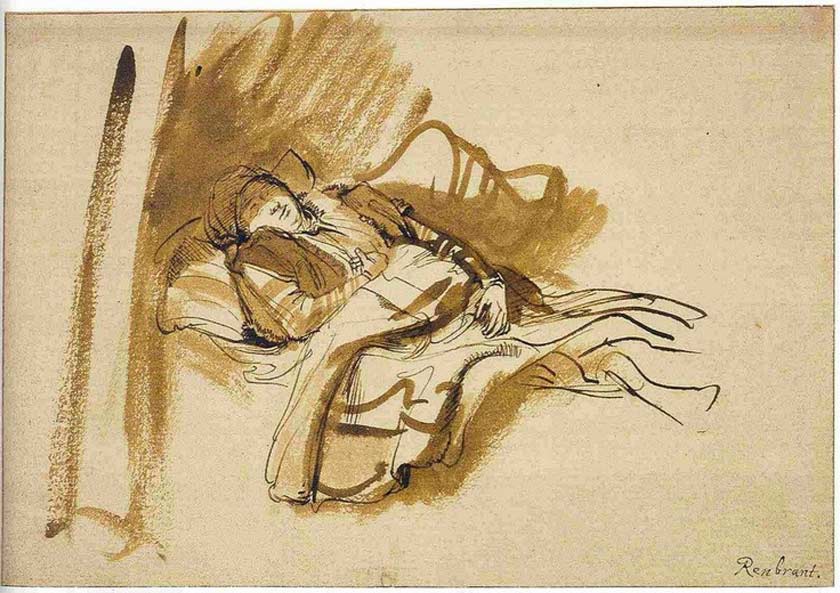

In around 1631, when Rembrandt was in his late twenties, he moved to Amsterdam, then the most prosperous port in northern Europe. He lodged in the house of an art dealer called Hendrik van Uylenburgh, and, while he was there, he met his landlord’s cousin, Saskia, who he married in 1634. He conducted numerous paintings and drawings of her in the first years of their marriage. He first drew her in the summer of 1633, just three days after their engagement, smiling at him from beneath the wide brim of a straw hat. After that, Rembrandt drew Saskia many times, often in intimate depictions of her having her hair combed, in bed, or sleeping.

Saskia also appears as a model in many of Rembrandt’s paintings. He accords a sense of grace to Saskia, depicting her personality in the portraits, that seem to change and adapt as their relationship developed. He painted her in expensive dresses, or as a classical goddess in a flowing dress.

In 1636, Saskia gave birth to the couple’s first son, Rumbartus. He died after only two weeks. Over the next four years, Saskia gave birth to two more children, who both also died within a couple of months of their births. Despite his personal tragedies, Rembrandt’s art continued to flourish, and in 1639, the couple moved into a larger, grader house.

In 1641, a fourth child, Titus was born, and survived. However, Saskia was unwell after the birth. In 1642, she made a will leaving Rembrandt and Titus most of her fortune, with the stipulation that Rembrandt’s share would be lost if he ever remarried. She died shortly after, aged only 30, most likely from the plague or TB, and Rembrandt was left alone with a young baby to care for.

Rembrandt was forced to take on a nurse to help him with his baby, and subsequently employed a widow called Geertge Dircx, who became his common law wife for a short time. He then took on another servant, Hendrickje Stoffels, and fell in love with her. Geertge took Rembrandt to court on the grounds that he had promised to marry her, but he charged her with pawning some of Saskia’s jewellery that had been left to Titus in her will, and had her sent to a house for correction. Rembrandt and Hendrickje lived happily together, however, the terms of Saskia’s will meant that he couldn’t afford to marry her.

Hendrickje appear in many of Rembrandt’s paintings from this period, including Hendrickje Bathing in a River of 1654, a tender and loving portrait of his current mistress. It is thought that this painting might be a sketch for a religious or mythological picture and that Hendrickje might be in the guise of an Old Testament figure such as Susannah or Bathsheba. The painting appears unfinished in some parts, for example, in the shadow at the hem of her dress and the right arm, however, Rembrandt was evidently happy with it and considered it finished since he signed and dated it.

In the 1650s Amsterdam was hit by an economic depression, and Rembrandt began to be chased by creditors for the repayments on his house. In 1656, he applied for a respectable form of bankruptcy that allowed him to avoid imprisonment, however, all his goods, including a large collection of his paintings, had to be sold off for very little money. Rembrandt, Titus and Hendrickje were forced to move to a much poorer district of Amsterdam.

In 1663, Hendrickje died after a long illness, and Titus was left to look after his father. Continuing financial problems forced them to sell Saskia’s tomb. In 1668, Titus married the daughter of a family friend, but tragically died seven months later. In 1669, Rembrandt himself died and was buried next to Hendrickje and Titus.

The tragedy that marked Rembrandt’s personal life never stopped him from painting however, and he continued to work up until his death.

References:

Cumming, Laura, ‘Rembrandt and Saskia: a love story for the ages,’ The Observer, December 30, 2018, theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/dec/30/rembrandt-350th-anniversary-saskia-portraits-netherlands-exhibitions

‘Rembrandt, 1606-1669,’ The National Gallery, nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/rembrandt

Learn time-honored oil painting techniques of the Old Masters!

What you will get:

- Instant access to all 60 multi-part video lessons

- A lifetime membership

- Personal coaching by the course tutor

- Constructive critiques of your artworks

- Full access to the Art Community

- Exhibition space in the Students Gallery

- Members-only newsletters and bonuses

- Old Masters Academy™ Diploma of Excellence

How you will benefit:

The Old Masters Academy™ course is very comprehensive, yet totally beginner friendly. All you need to do is watch video lessons one by one and use what you’ve learned in your creative projects. You will discover painting techniques of the Old Masters. This is the best art learning experience you can have without leaving your home. All information is delivered online, including personal support by the course tutor.