by Rosily Roberts

Joshua Reynolds works have, for over 250 years, prompted speculation and interpretation from art historians and conservators. His desire to be an independent and successful painter caused him to worry less about the soundness or durability of his technique, and increasingly about his capacity to manipulate the qualities and substance of paint in his emulation of the great masters of Italy. His technique varies greatly, from those painted in a straightforward manner to the highly complex multilayered compositions that defy interpretation or traditional conservation efforts. The first president of the Royal Academy, Reynolds was widely considered the leading portrait painter of his day, and a key figure in the Academy. His groundbreaking Discourses in Art, which was based on a series of fifteen lectures on art theory that he held between 1769 and 1790, were hugely influential in the development of British art. He argued that painters should look to classical and Renaissance art at their model, and that the idealization rather than copy of nature should be the aim of artists.

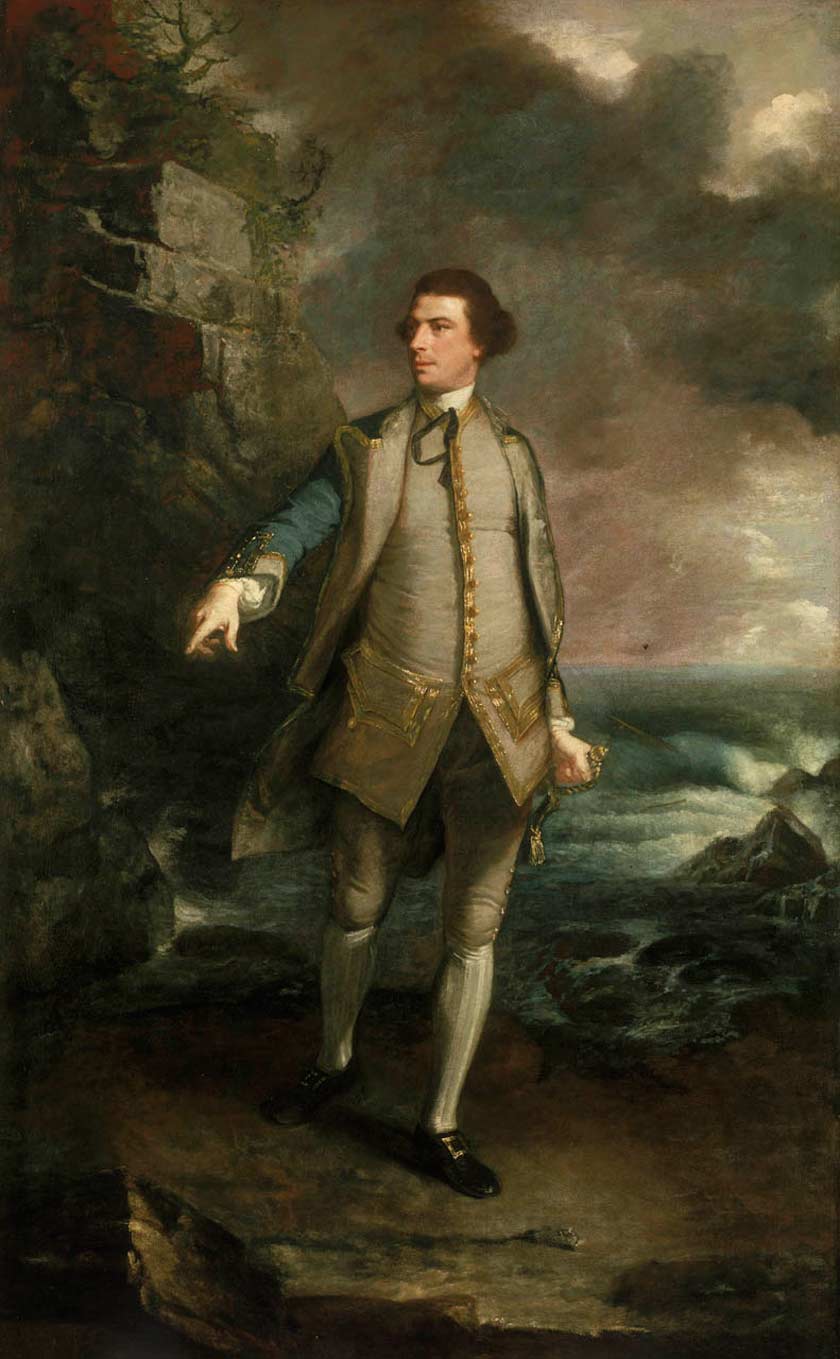

Reynolds used his knowledge of the Old Masters to inform many of his portraits, including, notably, his full-length portrait of Captain the Honourable Augustus Keppel of 1752 to 1753, in which the striding figure is based on the classical statue of Apollo Belvedere. While he was often criticised for his reliance on the Old Masters by other artists and commentators, patrons loved his works. Reynolds specialized in historical works depicting the present-day gentry as classical subjects, which ensured his rapidly growing popularity with patrons, who enjoyed being painted as mythical characters, which elevated both their personalities and the values they stood for. He felt that the artist should decide how to position his sitter in action or with an object that would best accentuate their personality. He strove to depict the sitter in such a way that viewers could relate to and understand them as a person. In an attempt to raise the status of portraiture among the arts, he developed what he called the ‘Grand Manner’ which borrowed from classical antiquity and the Old Masters to imbue his paintings with moral and heroic symbolism.

He typically did not make preparatory drawings for his paintings, nor did he generally use oil sketches to plan his designs, although both drawings and oil sketches do survive from his travels in Italy and Holland. He later referred to this works as sources for his own painting, having been deeply inspired by the work of the Old Masters.

He venerated the Old Masters for creating works which stood the test of time, and felt that no modern work could compete with such paintings. He noted the style and technique of many of the Renaissance masters, including Titian, Michelangelo, Tintoretto and Veronese, whose styles manifest themselves in his confident use of colour. He combined techniques such as chiaroscuro, the dramatic use of light and dark, and the classical contrapposto pose, in which the subject supports their weight on one leg. He worked to marry classical grace with naturalism, creating convincing, realistic portraits that retained a sense of poise and elegance.

He did not do traditional underdrawing for most of his paintings, preferring, instead, sketchy brushstrokes that loosely mark out the positions of his figures. His brushwork, by contrast, was tight and precise. He worked with smooth brushstrokes, and did not apply his paint heavily to the canvas, using long, hard, bold brushstrokes. He worked on a very large scale, which allowed him to be somewhat free with his brushstrokes, highlighting and darkening where he felt appropriate. He used a variety of brushes in various widths and lengths to help him create the finer details, particularly in his portraits. He ensured that the core lighting was always on the main figure and his background landscapes were also accentuated. He paid great attention to the background draperies, props and clothes, creating numerous folds and textures that helped define the light source and the depth of the picture, and added realism to his works.

The influence of Rembrandt can be clearly seen in his Self-Portrait of circa 1780, both in style and content. His pose owes a lot to Rembrandt’s own self-portraits, as does his dramatic use of chiaroscuro on his face. The loosely rendered tonal brown background also bears resemblance to Rembrandt. Reynolds, however, has included a nod to his classical influences with the bust in the background, partially obscured this his dramatic chiaroscuro.

References:

‘Joshua Reynolds Style and Technique,’ Artble,

artble.com/artists/joshua_reynolds/more_information/style_and_technique

‘Joshua Reynolds in the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection,’ National Gallery Technical Bulletin, vol 35, National Gallery Company, London, 2014

Learn time-honored oil painting techniques of the Old Masters!

What you will get:

- Instant access to all 60 multi-part video lessons

- A lifetime membership

- Personal coaching by the course tutor

- Constructive critiques of your artworks

- Full access to the Art Community

- Exhibition space in the Students Gallery

- Members-only newsletters and bonuses

- Old Masters Academy™ Diploma of Excellence

How you will benefit:

The Old Masters Academy™ course is very comprehensive, yet totally beginner friendly. All you need to do is watch video lessons one by one and use what you’ve learned in your creative projects. You will discover painting techniques of the Old Masters. This is the best art learning experience you can have without leaving your home. All information is delivered online, including personal support by the course tutor.